Hammerhead Sharks

by Uncle Charlie Maxwell

Maui Ocean Center Sea Talk, April 30, 2002

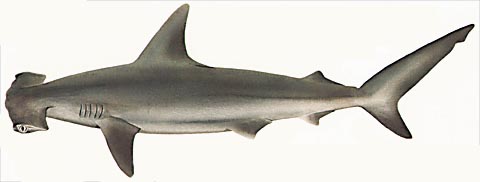

Out of all the sharks in the world, perhaps the easiest one to identify is the hammerhead shark, or mano kihikihi. Hammerheads are found in almost all of the tropical and warmer temperate waters of the world. Of the eight different species, three are known to inhabit Hawaii's waters: the scalloped, the smooth, and the great hammerhead sharks. Hammerheads have intrigued the world with their unique body shape and unusual schooling behavior.

It is plain to see how the hammerhead sharks got their name; their body shape resembles a hammer when viewed from above. There are many theories as to why the heads are shaped as they are, but there are no definite answers yet. One theory is that the enlarged head allows the animal to have increased sensory abilities. Sharks rely on numerous senses to find food, navigate through the ocean, reproduce, and other activities. Electroreceptive organs enable sharks to sense weak electrical fields given off by potential prey. They also use this important sensory ability to detect magnetic fields underwater, both from the North and South Poles and those created by volcanic activity, producing a type of 'highway' system on the ocean floor. When these receptors are spread over a greater area, it allows the shark to more accurately detect these electrical and magnetic pulses. Also, their olfactory organs are located farther apart on their head, giving them a greater volume of water to 'sniff' and make it easier to distinguish which direction a scent might be coming from. The actual shape of the head may aid in locomotion of hammerheads, providing lift or possibly a smaller turning radius. The hammer-shaped may also help the animal trap and hold its prey against the ocean floor. Scalloped hammerheads are always seen swinging their heads back and forth, maximizing the amount of gathered information.

The scalloped hammerhead, one of the most commonly seen shark by divers in Hawaii, has four lobes on the leading edge of the "hammer", and generally reaches between 5 to 10 feet long. As adults, scalloped hammerheads are usually found in the open ocean, often around seamounts, or outer reef slopes. The smooth hammerhead, named for the lack of scallops, is slightly larger, averaging 13 feet in length. The great hammerhead, reaching 20 feet, is one of the largest flesh-eating fish in the world, but is rarely seen in Hawaiian waters. Though hammerheads are not usually aggressive, they should be considered potentially dangerous.

One of the most fascinating characteristics of scalloped hammerhead sharks is its frequent schooling. It is the only known large shark to participate in this type of behavior. It is currently not known why they school, since the main reasons why smaller fish school do not seem to make sense when applied to the hammerheads. First of all, hammerheads do not have many predators, and predator avoidance is a major cause of schooling. Another reason why marine life would create a school is to surround prey, but most records show that hammerheads separate to feed alone at night. They eat a wide variety of food, including bony fish, rays, other sharks, squid, and octopus. Some schools of fish form during breeding season and broadcast sperm and eggs into the water, but hammerheads mate away from the schools.

The schools seem to be more social in composition, and may aid in mate selection. This may be important because scalloped hammerhead males are outnumbered six to one. Therefore, the majority of the sharks in the school are female, with the largest females located at the center. Since there is a direct relationship between the size of the female and the number of offspring, called pups, the males generally head right into the center for the largest female. The male will pick a mate and they will depart to breed in open water. A large female can bear up to 40 pups, while a shark in her first year of sexual maturity may have only 12 pups. Females will travel to shallow, protected waters in the spring and summer months to give birth. Before they are born, the embryos have flexible "hammers" that are bent towards the tails to facilitate birth. The pups are born live (most sharks lay eggs) and are generally about 17 inches long. Juveniles are not generally seen by divers, but are often caught in fishermen's nets.

Early Hawaiians highly revered sharks as both spiritually important and necessary for the health of the ocean. According to Charles Maxwell, Hawaiian Cultural Advisor, Hawaiians wisely understood the role of sharks in keeping the ocean clean by primarily feeding on the diseased or injured, or recently deceased animals, and did not commonly catch or eat them. Also, many families, or ohana, considered the mano to be their 'aumakua, or sacred guardian, which would protect the members of the ohana.

These facts remain true today, sharks play a crucial role in the health of our oceans and planet, and are still the 'aumakua of many families in Hawaii. However their populations are dwindling rapidly all over the world due to the strong international market for shark fins. Hammerheads are especially vulnerable due to their schooling behavior and the predictability of the schools' locations. Shark hunting remains largely unregulated, and if something is not done soon to change this, we may lose important members of the ancient world, and drastically offset the balance of our ocean ecosystem.